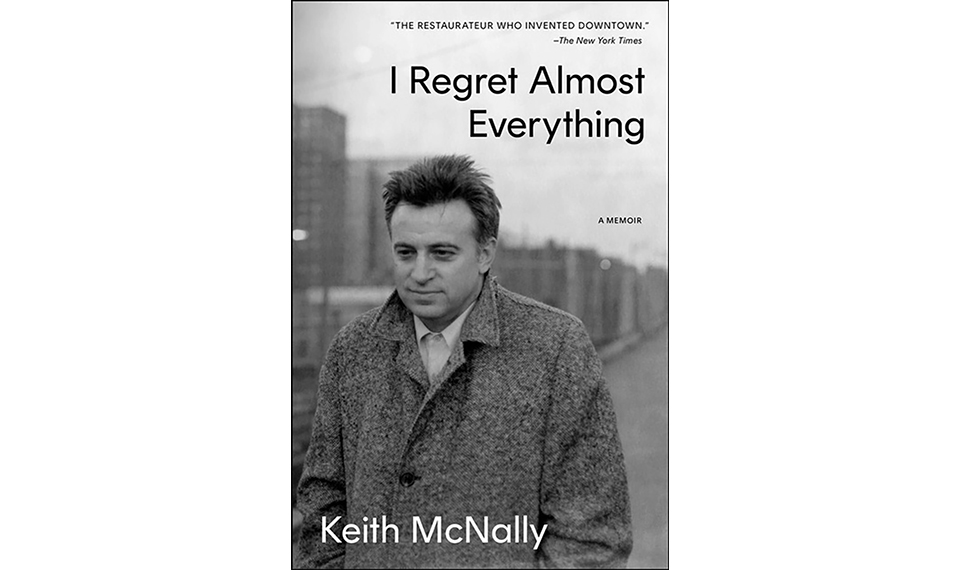

I Regret Almost Everything: Keith McNally talks with Richard Boch

Growing up in the Fifties and Sixties. Coming of age in the early Seventies and looking for a way out. Unsure of where things might be headed, though London, New York and Kathmandu are somewhere in the mix. Having no regrets or regretting nearly everything. Telling it all and not holding back, whether it’s your truth or the memory of truth. All this and more can be found in the deep scratches and below the surface of what becomes Keith McNally’s remarkable new memoir, I Regret Almost Everything.

Growing up in London’s rough-and-tumble East End well before the area experienced its version of gentrification, McNally was always hiding something. Somewhat unnerved by the disjointed relationship between his parents and the complicated relationship with his siblings, his search for identity and discovery were the forces that drove his life forward.

McNally found a bit of himself as a child actor in London and on the road touring the nether regions of England. He found companionship and friendship during that time while managing to live with the secret of a double life. Hitchhiking across Europe and Asia, it was a hippie adventure if not quite the dream he imagined. Arriving in New York City in 1975, McNally’s life and career began to take shape without fully realizing what was happening. Clueless when it came to the business of restaurants and hospitality, he found his break purely by chance when he was hired as an oyster shucker at the swank One Fifth in Greenwich Village. Moving quickly up the ladder, he eventually became the restaurant’s general manager. McNally hired his brother Brian, who had recently relocated from London, as a bartender. He hired his future first wife, Lynn Wagenknecht, as a waitress, and in 1980, the three of them opened The Odeon, which became not only a landmark restaurant and bar but a New York City institution.

McNally opened Balthazar in 1996, often considered his masterpiece but also one of the most famous restaurants in the world. From there, the list goes on and the story continues—some of which we may already know or will discover while reading McNally’s powerful, page-turner of a memoir. The family dramas, the crashes and the burn, the successes, the failures and of course the regretting—it’s all right here. The book is a voice of honesty and irony, allowing for moments where I sometimes laughed out loud and other times nearly shed a tear.

Life, love, passion and intrigue. It’s been a long journey of hide and seek, lost and found—and sometimes, despite the direct and occasionally brutal nature of McNally’s truth-telling, he may still be trying to hide what’s underneath. That’s where I found a truly compassionate and generous guy.

Now let’s see if any of that is even remotely true.

Richard Boch: Hi Keith. I’m really struck by the number of similarities that seem to balance out the differences in our childhood upbringings. Early on in I Regret Almost Everything, you talk about your mother not wanting people to know your family’s personal business. Speaking about emotions or feelings wasn’t really happening either. These imposed silences struck a chord with me, having experienced the same. Yet here we are in 2025, and you’re telling everyone everything. What made you so willing to expose the truth about yourself now? Is it a relief, or is there any sense of regret?

Keith McNally: I’m curious why you interpret my honesty as “exposing” myself. To really tell the truth about oneself involves wincing and cringing at your own behavior. Unless that happens, it’s not the truth you’re telling but a version of the truth designed to make you look good. I struggled with this throughout my book. To answer your last question… because there was no alternative, I feel neither relief nor regret to have written the truth.

RB: You mention there were times when you needed to hide something, whether it was in the school locker room, personal relationships, or other situations you were unable to be candid and open about. Did your days as a young actor show you a way to hide or be someone else, both on and off stage?

KM: Although “acting” is the correct metaphor for my behavior, as a job, it didn’t accentuate my double life.

RB: Do you still ever take cover behind a version of yourself?

KM: It’s a constant struggle.

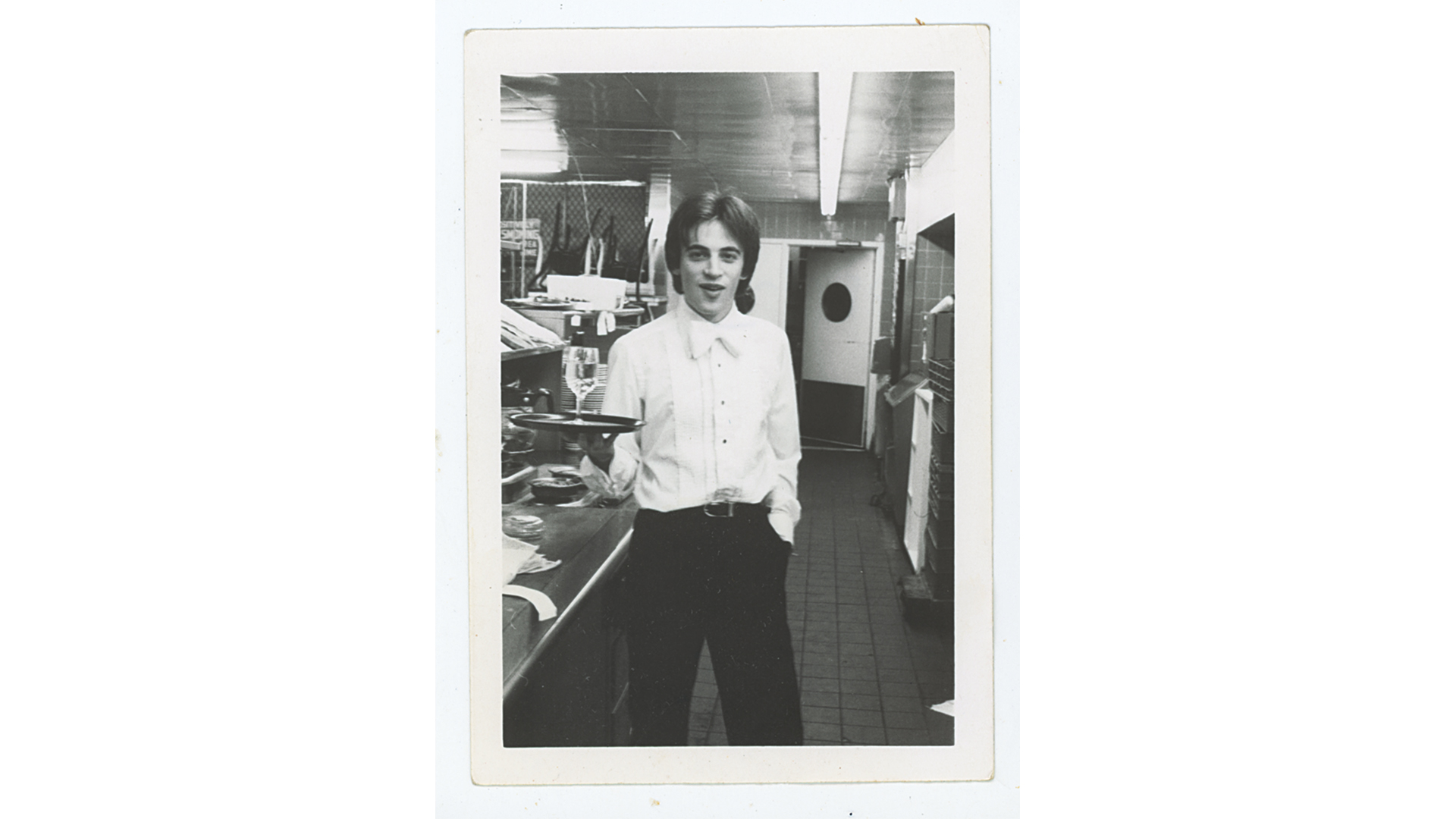

Kitchen at One Fifth, 1976. Photo courtesy of Simon & Schuster

RB: Leaving your boyhood home and never returning—and eventually moving to New York City in the mid-1970s would change your life in unexpected ways. So many of us come to the city with the intention of doing something very different from what we wind up doing. The young painter or actor who finds themself working in a restaurant is both reality and cliché, and I believe you can attest to that. Success and failure might exist in varying degrees and you talk about those variations in your book. How did it feel coming to New York to be a filmmaker and becoming what the New York Times called “The restaurateur who invented Downtown?”

KM: Ultimately, it felt disappointing.

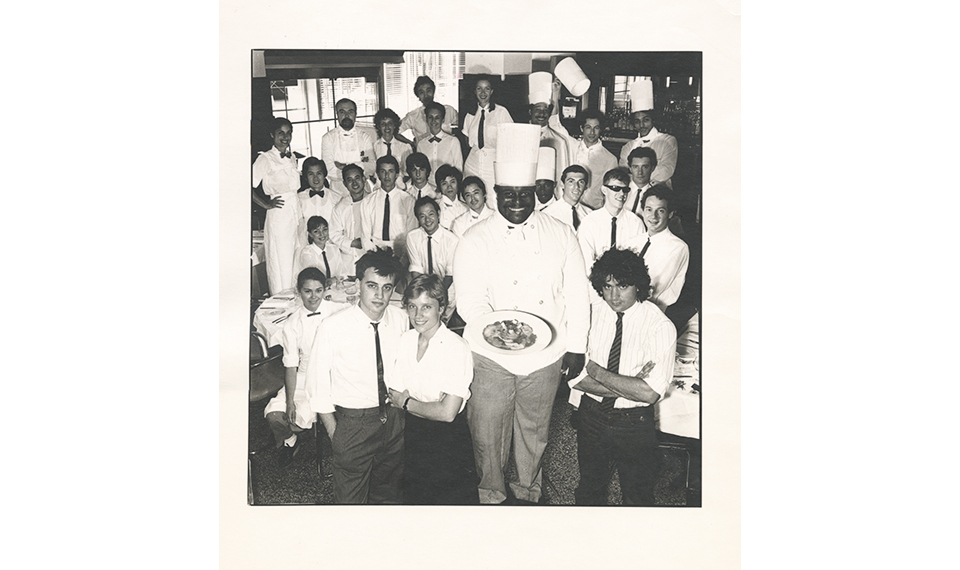

RB: After working a few years at One Fifth, you opened the Odeon in 1980 with Lynn Wagenknecht and your brother Brian. That was the new beginning. Café Luxembourg, Nell’s and Lucky Strike followed. There’s much more to come but was your creative itch being scratched (unapologetic cliché) by what you’d accomplished at that point?

KM: Though it was at times fun and exhilarating building and operating restaurants, it wasn’t fulfilling.

Odeon Staff. Photo courtesy of Simon & Schuster

RB: By the early 1990s, your marriage to Lynn ended, though you remain close, while your relationship with your brother Brian had become more challenging and somewhat competitive. You also wrote and directed several films during this time. Seems like a lot going on, yet within a few years, you opened Balthazar, often described as one of the best and most popular restaurants in New York. It’s also one of the most beautiful. Then, over the next several years, you opened Pastis, Morandi and Schiller’s Liquor Bar.

KM: I must put one thing straight. Though my relationship with Lynn these days is good—and occasionally very good—like many worthwhile relationships, it hangs by a thread. The same with my brother, Brian.

RB: So where did the regrets come in—and how did you deal with them?

KM: Suspicious more than regret. It’s not in my nature not to be skeptical about things I enjoy.

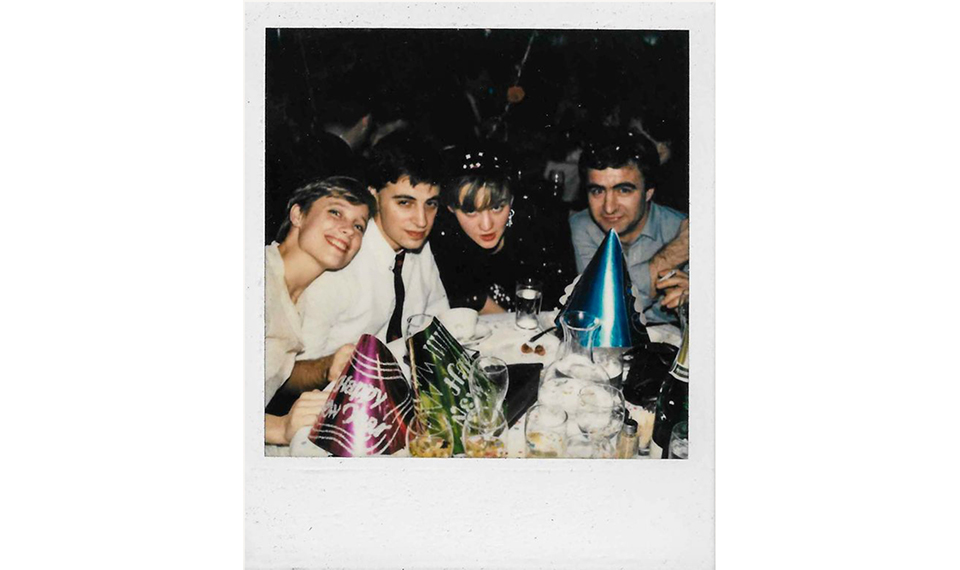

“Odeon’s first New Year’s Eve party. Lynn, me, my sister Josephine and my oldest brother, Peter” – Keith McNally. Photo courtesy of Simon & Schuster

RB: You relaunched the landmark Minetta Tavern in Greenwich Village in 2009 while continuing to open new restaurants and bars. You have five children—two with your second wife. You have employees who stay with you for a long time, and you treat them, for the most part, with kindness and generosity. Then, like everything else in life, something’s got to give. You had a stroke in 2016 that left you physically compromised, a personal crisis followed in 2018 and then your second marriage ended. Success was still in the picture but the setbacks were major. Regrets or not, is there a newfound sense of self-awareness after what you’ve been through and also by what you’ve achieved? You surely haven’t stopped being who you are, and that speaks to something about you. What is it?

KM: Until seventeen, I was the least self-aware person on the planet. But entering the world of the theatre and mixing with actors, writers and directors, I began to think about things in a slightly different way. Hitchhiking alone at nineteen to Afghanistan, India and Nepal, I became a lot more introspective and this, I suppose, was where my self-awareness really took hold. In my book, fearing the term “self-aware” is a bit highfalutin, I call it integrity. Moving to America at twenty-four with the intention of making films, I began building restaurants instead and, in the process, felt I’d squandered my integrity. I suppose this is the basis of my book. Forty years on, after my suicide attempt and nine weeks of forced hospitalization, my self-awareness returned in bucketfuls. And that’s what I drew on writing my book.

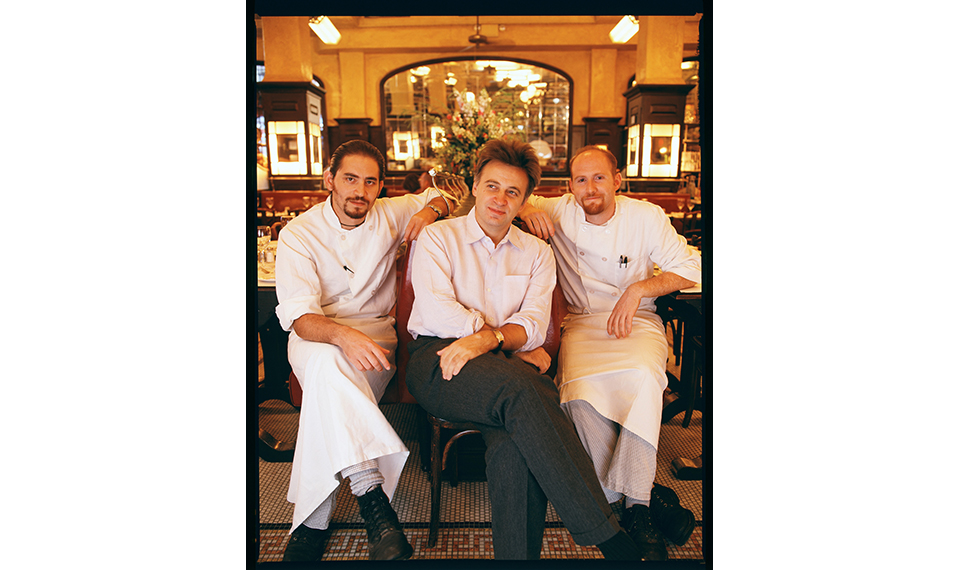

The Original Chefs Riad Nasr & Lee Hansen, 1997, Balthazar. Photo courtesy of Simon & Schuster

RB: Thanks for doing this, Keith. I also have to thank you for the quote that precedes the opening pages of I Regret Almost Everything. “Autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful.” That’s attributed to George Orwell who I dare not contradict, though reading your book, I experienced a sense of trust along with honesty and revelation—but no disgrace. Any thoughts on that?

KM: Though I feel a lot of regret, I don’t feel any disgrace. (Apart from doing this interview.)

RB: I need to add one more thank you after that last answer. So, thanks again.

***

Keith McNally was born in London and moved to New York City in 1975. In 1980, he opened The Odeon, the first of his many restaurants. He’s written and directed two feature films, End of Night and Far From Berlin.

His memoir, I Regret Almost Everything, was published by Simon & Schuster, May 2025.

WORDS Richard Boch

PHOTOGRAPHY Courtesy of Simon & Schuster

Richard Boch writes GrandLife’s New York Stories column and is the author of The Mudd Club, a memoir recounting his time as doorman at the legendary New York nightspot, which doubled as a clubhouse for the likes of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Debbie Harry and Talking Heads among others. To hear about Richard’s favorite New York spots for art, books, drinks, and more, read his Locals interview—here.